This is an audio zine by Jason McIntosh, speaking as Halstrick, about the Steam Deck video game console.

Rounding out the second season of Venthuffer is the episode about the origins of “Halstrick”, my relatively recent nom de jeu, as promised back in the zine’s earliest episodes.

When I began planning this episode last week, I thought it would be a memoir of my history with usernames, a meditation on the value of experimentation with chosen names, and the reasons I borrowed “Halstrick” from my late father.

Only the last of these made it into the final script. A cursory check about the name’s deeper history, which I thought would be lost to time, led to some tantalizing discoveries. Three days of research followed. The results are in the episode.

Things mentioned or alluded to in this episode:

- Guild Wars 2 Guardian and Warrior wiki pages

- The photo of “Uncle Joe” Halstrick held by my brother

- The Milstein Division of U.S. History, Local History, and Genealogy

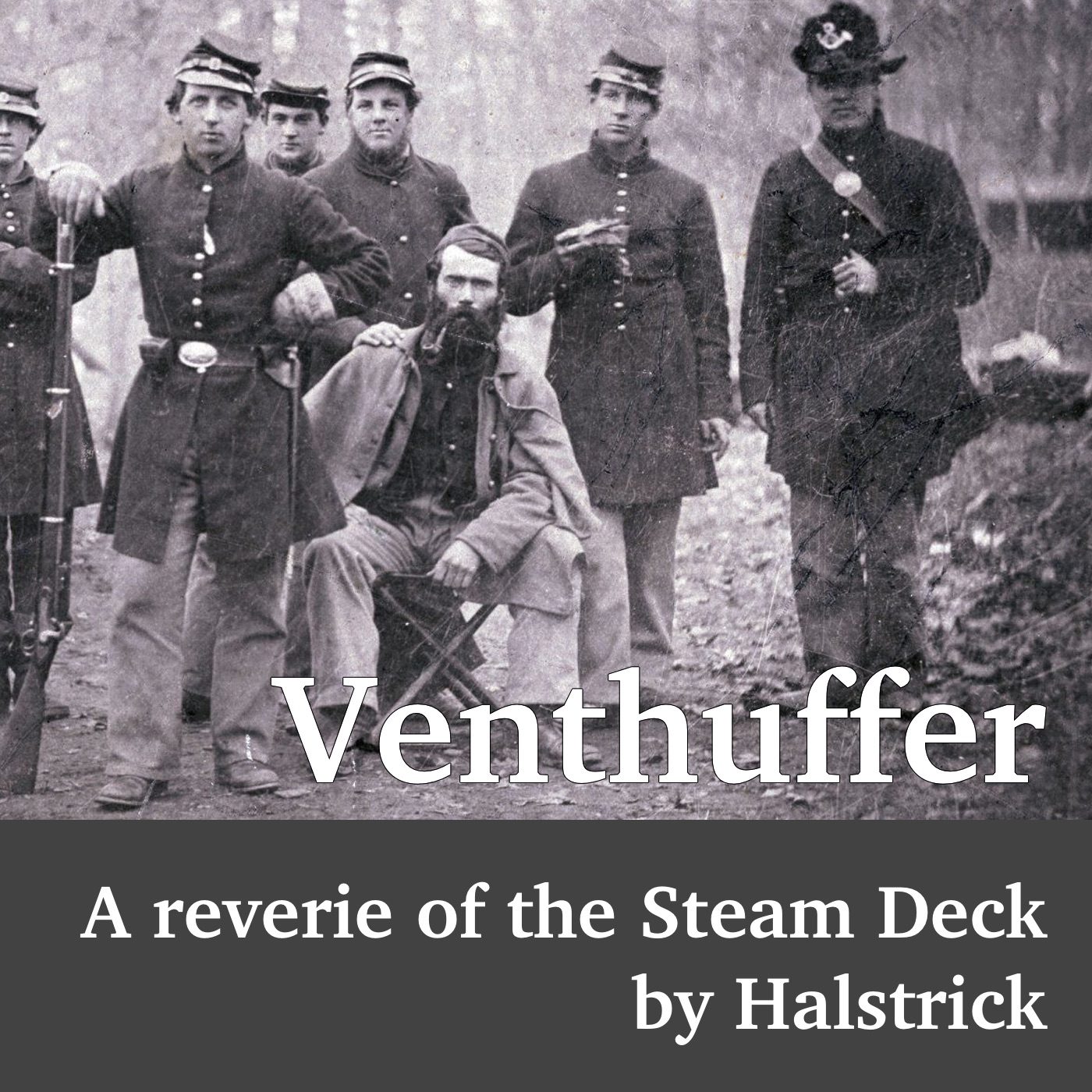

- An 1861 photograph of several members of the 13th Regiment of Massachussetts Volunteers

- Text extracted from A Complete History of the Boston Fire Department: Including the Fire-alarm Service and the Protective Department, from 1630 to 1888 at archive.org

- U.S. patent number 190,431 as a two-page PDF

- Report of the Chief of the Massachusetts District Police, 1895

- Joeseph Halstrick’s memorial page on Find A Grave

Full transcript:

As my father lay dying, I picked up his name.

This is Venthuffer, a reverie of the Valve Steam Deck, by Halstrick.

We arrive at episode 12, and the end of season 2. Before I take another break, I want to tell you about the name I use to produce this audio zine. I have used “Halstrick” as a general gaming handle since the purchase and setup of my first Steam Deck in late 2022. Since then—in fact, within the last few days of my recording this episode—I have learned so much more about the name. But before I get into that, I can share my personal history with it.

Halstrick was my father’s middle name. Growing up, I never thought about it much. I started thinking about it more in 2013, a year I spent largely in Maine, suddenly put in charge of both my parents’ end-of-life affairs, the details of which I shall spare you. This meant a lot of time alone in hotels, and I passed this time by getting into Guild Wars 2, an online fantasy epic. I rolled up two characters, a man and a woman, a guardian and a warrior. My mind being where it was, I gave them my parents’ middle names. I wasn’t trying for any kind of serious act of memorial; I suppose I just liked the nudge afforded by having the names always in-sight while I played, reminding me of my larger purpose, away from home.

Years later, I relocated from New England to New York, just weeks before the COVID-19 lockdowns, all of which felt like a definitive life chapter-break. After that, when I needed to choose a name for my online identity somewhere, I remembered that time in Maine, and I began to experiment with calling myself Halstrick. This included games with a more prominent social aspect, where other players address you by the name you present. And I found I liked being called by this name, one that sounds novel but not fictional, that has a pleasantly obvious shortened form, and with which I have a defensible real-world connection. So when the Steam Deck came, I took the plunge, and renamed my accounts on Steam and Playstation, and then Discord. Every platform or project concerned with gaming now sees me presenting myself as Halstrick—including the zine you are now listening to.

Before I launched Venthuffer, I did ask my older brother, who carries my father’s name in its entirety, for his permission to represent myself online using something that he holds the literal birthright to. He granted this permission, generously and easily. And in doing this, he reminded me that the unusual name wasn’t just made up at our father’s christening. My brother has memory of being told, as a very young child, about a man named Joe Halstrick, a Civil War veteran. My brother was encouraged by older family, all long gone now, to think of this man as “Uncle Joe”. But other than a single sepia-toned photograph that he’s kept safe all his life—depicting a middle-aged man with bright eyes and a period-appropriate mustache—my brother knows nothing else about him, or his connection to our family, or why our father was given his name.

Well, Uncle Joe did exist, but dad’s name didn’t come from him, at least not directly. I spent several days scouring the web, contacting more distant family members, and spending a long afternoon in the Milstein Division research room at the New York Public Library. Here’s what I learned.

Joseph Halstrick, Jr. was born in 1841 in Boston. As far as I can tell, he never spent any significant time away from Boston other than an eventful year or two in the U.S. Army, where he served in Company C of the 13th regiment of Massachusetts volunteer riflemen, joining at age 19. You can find a photograph of him standing among his company, in a small clearing by a tent in a forest. He stands in dead center, brimming with swagger, one hand on his hip and the other resting over the business end of his long rifle, which he’s planted into the dirt like a walking stick. He stares down the camera lens with what is unmistakably the same eyes from the photo my brother has, daring you to call him out on his questionable muzzle discipline.

Halstrick was wounded in action at the battle of Bull Run, and mustered out after spending the subsequent winter in the hospital, returning to Boston and resuming his work at his father’s silversmithing business. This trade would remain his central occupation for another 20 years or more.

But Joe Halstrick was not one to settle down early. Sometime around 1867, in his mid-20s, Halstrick joined Hose Company 5 of the city’s firefighters. According to the 1889 book A Complete History of the Boston Fire Department, he was very soon “badly burned in an explosion of hot air” while on-duty. I’m not sure whether or for how long he remained a firefighter after that; the book mentions him no further among company rolls. What I do know is that, exactly ten years later, Halstrick was awarded U.S. patent number 190,431. This described an adjustable attachment one could install on the era’s ubiquitous gas lamps, “producing greater illuminating properties with a lesser consumption of the gas”.

And some ten years after that, while in his mid-to-late forties, Halstrick changed careers, joining the Boston Police Department as a full-time inspector, specializing in factories. It seems strange today to think of a middle-aged rookie policeman, but I understand police departments around that time as undergoing a transition from citizen-watchmen groups into an organized, professionalized force. It’s not at all far-fetched that an experienced and decorated veteran, tradesman, and inventor—with a such a history of courage and resilience—would be welcomed as senior specialist in the new Boston Police.

Halstrick stayed in this role for over 20 years, keeping meticulous records of his inspections. Shortly before he retired in 1907, his service was cited in a journal of American child labor law enforcement, naming him as a member of one of the country’s few police divisions that actively monitored factories for exploitative hiring practices. After retiring, he stayed as busy as his flagging health would allow, showing up often at events around Boston commemorating the war, or the city’s fallen firefighters. Joeseph Halstrick died in 1915, at age 73, and is buried in Mount Hope Cemetery in Boston.

I am humbled and inspired by the life that Joe led. His demonstrations of heroic self-sacrifice for the sake of both his city and his nation speak of a character I can only hope to emulate in part. His mid-life career shift, after decades doing the job his parents wanted for him, resonates more directly, even uncannily, with the path of my own life. And the narrative implicit in his years-long quest to invent and publish a technology to save others from a terrible injury that he suffered? If I ever demonstrate a fraction of that drive on a personally meaningful project with global benefits, my life will have been worth living.

But none of this explains how my father, born and raised in the small community of Rockland, Maine, 200 miles up the coast from Boston, ended up with Joe’s name fifteen years after his death. And this where the women come in.

My aunt told me about my great great aunt through my father’s mother, named Cora Halstrick. I had found her obituary in the library, the day before, naming her as the widow of Joseph Halstrick of Boston. She had died in my father’s hometown of Rockland Maine in 1939, overlapping with dad’s life by a few years. My aunt recalled my grandmother speaking of Cora with affection and gratitude; she played an active role in helping to care for my infant father, and his brother—and their mother. And so that’s where my father’s name is from. The name is from Cora, a handprint of the love and care she showed my young grandmother’s family, one that my older brother still carries almost a hundred years later.

This is not to eclipse Joe: Cora clearly remained deeply fond of her late husband, carrying several of his treasured affects and mementos with her to Maine. She told her niece about Joe, and many years later her niece told her children about Cora and Joe both, and eventually told her grandchildren too. My brother still has that ancient photograph from these tellings, surviving the clouding of time over memory.

But I must acknowledge how, in accordance with the diminished visibility of women in the public record, the only documentation I found of Cora was of her passing, listing no details of her life or accomplishments other than her marriage to Joe. I couldn’t even find a wedding announcement about them.

I did find another news blurb announcing Joe’s marriage to a woman named Mary Packard in 1868, a year after his injury in the explosion. Did this accident lead to their marriage, somehow? Did Mary encourage Joe to apply his mind to translate his pain into invention? How much of the patent might be co-credited to her, in fact? What happened to her? How much of his life did Joe spend with Mary, and how much with Cora?

I hope to know some day—honestly, I hope to make some field trips about it—but right now, I don’t even have enough information to speculate. The treatment of the Halstrick women in the records I found is so frustratingly curt as to be almost funny. Joe’s obituary in the Boston Globe mentions neither Cora nor Mary; another paper’s note about his passing states only: “He leaves a wife.” In a who’s-who book I found about notable Boston residents dated to the closing years of Joe’s life, there is a listing for “Mr. & Mrs. Joseph Halstrick”.

So here are those who held the name, together: a 19th century Bostonian who led an astoundingly full and meaningful life, his surviving partner who subsequently went to Downeast Maine and directly helped my grandmother’s family flourish, and another woman whose story is rich with potential but painfully obscure. I didn’t know any of this a week ago. What am I to do with it all?

Well, I’m going to keep the name. My father didn’t like to talk about his past, or his family. He never suggested what his middle name meant to him, and he died before I ever thought to ask. My research unearthed not just the life story that I was hoping to find, but a story of people who cared deeply about family, and community, and civic duty.

None of this has much to do with video games. I started using Halstrick just to keep dad in mind. Then I used it because it sounded cool on the internet. Now I want to keep holding the name, specifically because I know more about the basic goodness that it represents.

I have studied and written about video games for my whole life so far, and I’ve come to accept that that’s how the rest of it going to play out. My main lens for examining games these days is less as challenges or passtimes and more as art, as communication, work made by people for other people to comprehend, transferring perspective through play. And I feel so lucky that I have the chance to continue my personal game studies under an already-adopted name that is so weighted with bravery, and ingenuity, and caring.

This has been Venthuffer. You can learn more about this show, find links to the things I mentioned on this episode, or subscribe, at Venthuffer dot com. If you enjoy this show, tell your friends. I’m taking a break after this episode, and plan to return with more Venthuffer later in 2025. Be well, stay playful. And you can find me, on Steam, as Halstrick.

Through sheer luck I happened to overhear an offhand mention of a new Llamasoft game, a remake of an obscure coin-op from the 1980s with which I happen to have a peculiar history. This leads me to reflect on one of the longest still-active auteur careers in video games, and ask the question: Who are Jeff Minter’s games for, actually?

Things mentioned or alluded to in this episode:

- Jmac’s Arcade on I, Robot (1984) on YouTube

- Space Giraffe on Wikipedia

- Tempest on Wikipedia

- I, Robot (2025) on Steam

- Tempest 2000 on Wikipedia

- Psychedelia on Wikipedia

- Neon on Wikipedia

- Gridrunner on Wikipedia

- “On Authorial Intent and Space Giraffes”, a 2008 blog post

- Polybius on Wikipedia

- Tempest 4000 on Wikipedia

- Ian Malcom’s Mastodon post about I, Robot

- Llamasoft: The Jeff Minter Story homepage

- Jeff Minter on Mastodon

The cover artwork for this episode uses the image “Giraffe over the Horizon” by bobosh_t, licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0 .

Full transcript:

In 2007, I recorded the penultimate episode of Jmac’s Arcade, a reminiscence of the all-but forgotten video game I, Robot. This is a bit of what I had to say at the time:

“Though I didn’t play it much at the time, apparently my experience of seeing it in the arcade is unusual; it was a pretty rare machine, and how one would make its way to the Bangor, Maine game room I frequented I’ll never know. […] The game itself is actually pretty fun. Despite the title, the story—such as it is—is more Phil Dick than Asimov, with some Orwell thrown in for flavor—the game was released around 1984, after all, a year which contained as many winking references to its namesake novel as you might imagine. Stylistically, the game’s a 3-D platformer in its most literal sense…”

Ah, I was in such a rush to get the words out, back then…

Also in 2007, Jeff Minter celebrated a quarter century of being the video game world’s best known ruminant-obsessed creator with his company’s release of the psychedelic shoot-em-up called Space Giraffe. Hobbling out on knobby knees, it clattered onto Xbox, the game console I was most interested in at the time. The reception was nonplussed, at best. Most gamers of the day did not know what to make of an acid-house alternate-universe take on Tempest, one full of quite intentionally impenetrable visuals: as much a neurological hack to shock the player into a flow state as a traditional game with scores and levels. According to Minter, it was outsold ten-to-one by another publisher’s simultaneous remake of Frogger.

In 2025, Llamasoft—the game company helmed by Minter and his partner Ivan Zorzin—quietly released another game whose lineage passes through both Space Giraffe and I, Robot. In fact, it’s called I, Robot, and it’s presented as a remake of that forgotten game from 1984, the same one I recorded a monologue about just as Space Giraffe started to ship to a world of unready Xbox fans.

And you know I couldn’t let that pass without comment.

This is Venthuffer, a reverie of the Valve Steam Deck, by Halstrick.

Playing I, Robot on my Steam Deck with my headphones clamped on, letting my whole sensorium be battered by pulsing visuals and squealing sound effects as I fought to gain a sliver of comprehension about what I was even doing, I had the thought: Jeff Minter is the Miyazaki of… whatever this is.

Building on an early career that helped define the scrappy UK gaming scene in the 80s with innumerable titles about mutant camels and stolen lawnmowers, Minter made a worldwide splash in 1994 with Tempest 2000 for the Atari Jaguar console, a remake of Dave Theurer’s classic arcade shooter from 1981. Minter’s other creative passion involved creating music visualizers, or what he called light synthesizers, going all the way back to a simple demo called Psychedelia for the VIC-20 home computer in 1984. Some 20 years later, he co-developed Neon, the music visualizer built into the Xbox 360 console, and and this swiftly became the graphical basis for the full-court audiovisual chaos of Space Giraffe. The game’s mechanics are clearly inspired by Tempest, but Minter has always insisted that Space Giraffe is not a followup game, but its own bizarre beastie.

Despite whatever disappointment Llamasoft might have felt from the game’s divisive reviews, Space Giraffe clearly set the course for Minter’s subsequent work. Now co-designing with Zorzin, Minter led Llamasoft into a prolific post-Giraffe period that continues through today, releasing scads of new work for mobile and console platforms, all bursting with the same intense energy, immediately identifiable by their mix of hyperstimulating visuals with barnyard-infused soundscapes.

I had largely missed Minter’s first act in the 80s—I did enjoy the Atari 800 port of his first international megahit, Gridrunner, but I was too young to feel particularly curious about its authorship, and none of his weirder games about mystical goat-men and cosmic hover-sheep could easily reach a kid in the US. But by the aughts I had become aware enough of his name to pick up Space Giraffe with interest, and followed the controversy around it with enthusiasm, even spooling out some blog posts about how the fallacy of authorial intent applied to Minter’s defenses of the game’s perceived inscrutability.

And, since then, I have bought every Llamasoft game I could: the reboot of Gridrunner for iPhone, the VR madness of Polybius on my PlayStation 4, the inevitable Tempest 4000 on Nintendo Switch, and now I, Robot on my Steam Deck. The launch of each one felt like a reason to celebrate, like a band you loved in your youth dropping a new album unexpectedly.

This despite the fact that I haven’t really loved any of this work! I’m not sure I’d call any single title a great game. But I recognize the whole collection as part of something profoundly important, and worth paying for, and experiencing, and even studying.

The most salient study question is this: Who are these games for?

To a first order of approximation, nobody in earshot of me mentions a new Llamasoft game launch, despite the legendary status of its head designer. In 2025, Minter has been a globally recognized auteur for more than 40 years, and yet I heard about I, Robot through a single offhand Mastodon post by veteran game designer Ian Malcolm. The subject of that post, in fact, was Malcolm expressing pride at attaining a top-25 spot in the new game’s global leaderboards, and acknowledging that this was only possible due to the combination of novelty and obscurity that he has come to associate with all Llamasoft releases.

Who is I, Robot for? Few people know about the original 1984 arcade game, fewer have seen it—let alone played it in its original cabinet—and I would hazard that fewer still know that its designer, Dave Theurer, was the same talent behind the orginal Tempest. I seriously wonder if the number of living people who can join me in claiming all three is larger than a dozen people. It can’t possibly be more than a hundred.

So, if I wanted to, I’d have ground to claim that I, Robot is for me! Beyond the connection to Theurer’s original game that I’ve felt since 2007, the Llamasoft rework has more deep-cut references that delight and astound me, such as one level that is an explicit homage to Amidar, another primordial arcade game from 1981.

But the truth, of course, is that I, Robot—like every other game from Llamasoft—is for Jeff Minter. The excellent 2024 interactive biopic “Llamasoft: The Jeff Minter Story” opens with an epigraph, quoting an old magazine ad: “He makes ‘em so he can play ‘em.” Minter isolated the elements that he loved about video games and music with his solo work in the 1980s, and all of his team’s output since then has been iteration and refinement using these same elements, again and again. Minter has welcomed all the intervening advances in game platform technology, but has used them strictly to dive ever-deeper into realizing his narrow and uncompromising vision for what a good game is, combining frenetic action with electronic dance beats, psychedelic colors, absurdly chatty text, and a vast collection of sampled ancient-arcade bleeps and hoofed-mammal chatterings.

Jeff Minter is hardly the only active game designer making deeply personal work today. But very few creators in this space have such a lengthy ludography, one that has attained an astounding depth of expression by mindfully limiting the breadth of its interest. Theuer’s I, Robot had a frame story about a plucky little android rebelling against the watchful eye of Big Brother, staying one step ahead of its wrath. Minter’s I, Robot does away with all that, and signals the fact by sticking a pair of ovine horns on the robot’s head, making its only mission the ever-deeper furtherance of the Llamasoft oeuvre.

I have the impression that Minter’s focus is driven less by obsession than joy. He has been a prolific poster to social media since the publication of Space Giraffe during the LiveJournal era. I have followed him off and on over the years, through Twitter and now Mastodon, tagging along as he wakes up, brews tea, tends adoringly to his flock of pet sheep, and then goes to the pub for a curry. Every now and then he might head into town for a show—maybe Underworld is touring again! Somewhere in there, he makes games, or codes up game-adjacent doodads, and posts hints and scraps of them. All of these things make him happy, and he enjoys sharing them. Again and again, every day, across years. I think he might be one of the happiest people on the internet.

As I record this, my plays of I, Robot last only a few minutes, all my lives draining out on the presently inexplicable level five. I can’t yet claim any profound connection with the game. But I take such energy and inspiration from its role as the latest step on a brilliant artist’s personal creative journey, one that I feel very fortunate to coincide with. The ongoing work of Minter and Zorzin has so much to teach me about the primacy of finding what things bring you joy, and—as much as possible—simplifying your life down to their daily practice. Of continuously exploring and refining yourself, through focused, iterative, and meaningful creation. And, maybe every few years, releasing a bit of that into the world, to dance on its own, with colors radiant, and swirling, and wooly.

This has been Venthuffer. You can learn more about this show, and find links to the things that I mentioned in this episode, at Venthuffer dot com. If you enjoy this show, tell your friends! And you can find me on Steam, as Halstrick.

“Good enough for your eyes and mine.” Applying Depression-era thinking to modern hardware upgrade cycles.

Things mentioned in this episode:

- “Everything can can be invented has been invented.”

- Agmena Paneuropean Book, the typeface used by Elden Ring

- The $485 Volume Knob

- Godot, an open-source game engine

Full transcript:

“Resolution”

I am told that the Steam Deck has a resolution of 800p. I’m sure I’ve read exactly what this means, more than once. And every time I let myself forget it soon after, lest the knowledge tempt me to gracelessly yearn for a counterfactual world where that number could be bigger, leading me away from satisfaction with the marvels and wonders already in my hands.

This is Venthuffer, a reverie of the Valve Steam Deck by Halstrick.

My father—from whom I derive my nom de jeu—was of the breed of conservative American dad who—perhaps by dint of a childhood that overlapped with the Great Depression—didn’t cotton to the notion of upgrading perfectly acceptable hardware. “Good enough for your ears and mine!” he’d say whenever one of us kids suggested a replacement for our home’s Kennedy-era stereo system. “Good enough for your eyes and mine!” he’d say as we pointed out opportunities to think a little bigger with our collection of mid-century televisions.

I think I understand where he was coming from. My father lived in a world of binaries, as far as property and possessions were concerned: either you had a thing, or you did not. If you did not have a thing, and you needed it, then by all means, work to acquire it. But if you did have a thing, and then you act as if you didn’t, pining for a slightly shinier version of the same thing? Then, son, you need to check yourself, because you’re on a path of eternal dissatisfaction, refusing to ever feel happy with what you already have.

I think of dad’s dismissal whenever I hear speculative talk about game console upgrades—which, of course, has lain thick around the Steam Deck almost since the day of its launch. The system has enjoyed a few improvements in its first couple of years, gaining an OLED screen and more generous storage while shedding a bit of weight—but nothing so drastic that you’d call it the Deck 2. And yet, I have absolutely witnessed friends stating that they’d like to have a Steam Deck but will wait until they can buy its successor—a system which, at the time of this recording, has not even been hinted at by Valve.

I understand the impulse. Barring unforeseeable drastic changes in consumer-electronics paradigms, we can surely expect the Steam Deck’s official followup to arrive some day. But I temper this expectation with my strong belief that any single aspect of consumer technology advances along a sigmoid curve.

Back when I was really into Apple hardware, millennial Macs and early iPhones especially, one felt the vertigo of living in the steep middle of that curve. The upgrade cycle was not merely inevitable; it was exciting! I’d hang around websites with gorgeous charts and graphs pinpointing—with evidence!—precisely where on the historically proven cycle every major Apple product sat, letting you plan your next upgrade so as to maximize the lifetime of each purchase.

Beyond the fact that this approach encourages a definition of “lifetime” which states that your computer or other gadget drops dead the moment a fancier model becomes available—the sort of thing that would earn withering skepticism from my father, “What, did it stop working? I hear you typing away on it every night!”—I think that when it comes to squeezing more meaningful power out of microprocessors, we rounded the top corner of that curve many years ago.

At risk of sounding like the proverbial nineteenth-century patent officer who declared that everything worth inventing had been invented, I really do get the sense that few technological barriers still exist to prevent the realization of worthwhile game concepts. We can figure out more ways to pour more simultaneous polygons into a game world, letting them individually render every eyelash on your character’s face as they blink away raindrops which each have runtime-computed trajectories, but none of this contributes to the truly engaging and long-term memorable elements of a game, the stuff generated only by the creative muscle of human minds.

Sometimes—rarely, but sometimes—advances between two major platform revisions do represent true leaps across a quantum threshold.

My current paternalistic grouchiness about upgrades came about in the run-up to the PlayStation 5, when I still felt utterly floored by the abilities of the PlayStation 4 I had received for Christmas many years prior. I saw nothing but a cynically commercial ploy in enticing people to drop another thousand dollars or so on a new box, controllers, and other clattering, miscellaneous plastic in order to enjoy barely-perceptible improvements in graphical rendering.

But then, of all people, my manager at work—a former games journalist—sat me down and explained the true differentiator between this console generation and the previous. That was the presence of solid-state storage, a marvelous looping-back to past eras of games burned into ROMs and cartridges, where the loading times of games’ increasingly vast data sets were no longer constrained by physically spinning media. Solid-state drives don’t improve the frame-to-frame appearance of any game, but they do vastly improve the overall experience of spending time with any interactive work recent enough to require load screens.

I was convinced and that sold me on… the Steam Deck, actually. And shortly after that, I purchased the Steam edition of Elden Ring, even though my family already owned it for our PlayStation 4. And I saw the look of astonishment on the face of my partner, who had perished a thousand times in the Lands Between, as my own gurgling deaths were reset in moments, rather than a full minute, I felt satisfied with that upgrade.

At the same time, I was aware that, as much as Elden Ring on the Steam Deck absolutely runs good enough for your eyes and mine, something about it still looked off compared to the PlayStation. Presently I realized that it was the text: the game’s use of a tasteful, serifed, variable-stroke typeface looks wonderfully evocative on a traditional console. But on a Steam Deck pushing its video out to an external display, any flourishes of text become reduced to juddering, palsied jags. It’s still readable, but it doesn’t look great. And sometimes it isn’t even readable, which can all by itself lead to Valve to stamp a game with that timorous yellow dot of partial Steam Deck verification, instead of a green checkmark.

I know what kind of games I like. And as much as I luxuriate in amazing effects of computed sunlight filtering through breathtaking artificial mists, my ongoing attention will always be on mini-maps, and inventory readouts, and journals full of scrawled intrigue, and on and on. I need those small, flat symbols to look as crisp as they can, as round and healthy as the dialog of a Zelda character on first-generation Nintendo Switch. My understanding is that the fixed resolution of the Steam Deck is a trade-off that optimizes gameplay on the handheld system’s built-in screen, and which allows output to much larger displays, but only after passing through an up-scaler that’s prone, by its nature, to lose fine details. I find this acceptable for screen-filling landscapes and character models, and less so for text, where details carry information.

And so the expensive particle-effect mists part to reveal the frontier of what might actually entice me to upgrade, when the day of Deck 2 arrives. My internalized emulation of dad’s skepticism could concede the point, and allow an agreement.

For all that, my father’s brand of conservative confidence has the disadvantage of a certain closed-mindedness, one which can manifest as a blindness to the value of other peoples’ interests, compared to one’s own. On my first draft of this monologue, even as I confessed to my own hunger for better text rendering, I had decried the pursuit of optimal frames per second (FPS) as a foolhardy obsession among a certain class of videogame enthusiast.

The Steam Deck caters to this sort of twiddling, making it easy to tune the maximum FPS of individual games. I once set the FPS of Elden Ring from one number to a different number, following the advice of a popular online guide, and experienced—no obvious difference at all, leading me to dismiss the whole statistic as a kind of pseudoscience, the equivalent of hi-fi aficionados arguing over which kind of wooden stereo knobs contribute to the richest sound.

But then, between that draft and this recording, I started a weekend project of learning the open-source game engine known as Godot. This exposed me to several fundamentals of how modern video games work. And here’s where I learned that frames-per-second is a fundamental unit of measure for a game’s processing loop, including the speed at which it can poll and respond to player inputs. This can have much greater effect on the quality and playability of a game beyond its mere appearance. It can even affect how much energy a game requires to run, something of naturally particular interest to Steam Deck players!

This doesn’t mean that the stat-juggling hobbyists are always wholly correct in the depth of their meta-gaming focus, but I have come to respect that their obsessions—which include speculation about how a new Steam Deck might better support higher FPS rates—aren’t without merit.

Between my acknowledged longing for cleaner text rendering and my lesson in humility that I don’t, in fact, know everything about the potential of all future game technology, I can arrive at a place where I summon a measured portion of my father’s sense of satisfaction with the present. Letting the future arrive whenever it will, I shall neither squirm with unseemly anticipation, nor resist the possibility of unforeseen promise. When the inexorable opportunity to upgrade does come, I can resolve to meet it with my eyes open.

This has been Venthuffer. You can learn more about this show, and find links to the things that I mentioned in this episode, at Venthuffer dot com. If you enjoy this show, tell your friends! And you can find me on Steam, as Halstrick.

Recalling the time when House Flipper forced me to take a hard look at a real-life household crisis brewing behind the refrigerator.

Things mentioned in this episode:

- House Flipper on Steam

- German cockroach (Blattella germanica) in Wikipedia

Full transcript:

A word of caution. In this episode of Venthuffer, I talk about creepy crawly things. If you’re not in a mode to hear that sort of thing right now, maybe come back to this one later.

In the summer of 2023, I put a household dilemma out mind by trying an interesting game, not expecting that it would directly simulate the very problem I had hoped to buy a bit of escapism from.

Not only did it surprise me into seeing my local crisis from a new angle, but it presented me with the keys to its own solution. To defeat the monsters plaguing my home, I had to become the NPC, and hire the hero.

This is Venthuffer, a reverie of the Valve Steam Deck, by Halstrick.

What drew me to try House Flipper, five years after its 2018 release? It’s in the peculiar sub-genre of games that simulate bootstrapping and then growing a business doing something that’s actually rather rote and labor-intensive, a category including games like American Truck Simulator, or even Stardew Valley. As suggested by its title, you succeed in House Flipper by buying homes for cheap and selling them at a profit, but you spend most of your gameplay time cleaning up and remodeling the broken-down, gutted, weed-choked dumps that you acquire before releasing them back into the market. And this is all done by hand through a first-person interface that has you do everything from cleaning out cobwebs to repainting walls to buying and installing new furniture and appliances for every room.

Well, for some time, I had been curious about the potential for a highly specific simulation game like House Flipper to present not exactly a transfer of real-world skill, but of a highly suggestive experience. That the ideal, anyway! The player has to accept that simulating the magnitude of the labor and the logistical complexities of running a real-estate business—to say nothing of its legalities!—must involve significant abstraction, compared to what one sees in a more mechanical and objectively verifiable simulation, such as in a flight simulator.

But I was also drawn to this game’s specific theme because of my parents’ career while I was growing up. Their work predated popular-culture use of the term “house flipping” by decades, but it’s what they did for my whole childhood: we’d all move into some junker of a home, which my parents spent a year or two fixing up as their primary shared project, and then we’d all move on to the next one.

So when the game went on sale while during an extended home-alone period, while my partner was in Chicago for a professional conference, I spent a full evening or two in the world of House Flipper. I could quickly see its appeal to “satisfaction” in the social-media brain-rot definition of the word, giving you a chaotic environment and the tools to make it orderly, step by step, letting the work—and its immediately visible effects—serve as its own reward.

But while I can acknowledge that attraction, I don’t really resonate with it. I could tell that progressing very far into the game’s simulated career path would be a slog, and that I’d lose interest in the game once the novelty passed. But my reasons for trying it remained, and I decided to stick with it until I had the basics down, enough to flip my first house and at least enjoy some sense of the fulfillment promised by the title.

And that’s where I found a point of crossover.

Listener, here I must make a confession of which I’m not proud at all, but my story hinges on sharing it. At this time, our upper west side apartment was experiencing a cockroach infestation. German cockroaches, if you need to know. The little ones.

It started small. We are both experienced urban dwellers and had had our share of unwelcome arthropod incursions plenty of times. So we deployed the usual drugstore tricks and traps and didn’t worry about it too much. But, by the time my partner left for her trip, it was clear that, for the first time, the invaders were outpacing our casual countermeasures.

Look: as far as I can tell, they never got into our food. I have my suspicions about what they were eating, and I’m pretty sure they were taking water from the cats’ dishes as well as our freezers’ ice trays, but they left our food alone. And they never got into our bedroom. But none of this lets me deny how, in the wee hours of every morning, the rest of our small apartment’s floor would roil with cockroach rush hour, streams of skittering commuters fanning out from multiple bases of operations they’d clearly set up in dark places. The only ones I managed to find myself, quite by accident, were the battery compartments of my cats’ automated feeders.

All this was going on while I played around with House Flipper. So when, early on, one of the fixer-upper problems you encounter in the most vile of abandoned squats is roaches, I sat up a little straighter. The game simplifies it, of course, as it simplifies every aspect of refurbishing a home, but it contained two startling kernels of truth. In House Flipper, you play a professional who knows better than to fight a roach infestation by squishing individual bugs, or by merely laying out some store-bought traps and calling it a day. No, the House Flipper player-character heads straight to the nest, and pulls out their vacuum cleaner. That is to say: There are nests, and you can destroy them directly.

House Flipper is, by its nature, a meditative game. I had plenty of time to think as I cleaned up that wreck of a dwelling, sweeping up its broken glass, hauling out its greasy pizza-box stacks, and methodically dismantling all of those… nests. By the time I had finished my virtual labors, I had also sat with the truth of how the game’s predicament overlapped with my own. And that’s the moment when I realized. That strange, almost sweet smell that had been wafting from the strangest places in our apartment over the last couple of months. Oh. That… was the real-life version of the on-screen prompt that tells you to hold the left trigger down, to bring up your toolbox radial menu and select the vacuum cleaner. It had been flashing at me for weeks and I didn’t understand it, at least not until I stumbled upon its digital translation.

And so when I was done with that in-game mission, I powered down my Steam Deck, and I made the inversion. Reaching through the sleeping screen and pulling the game’s reality inside-out like a sock, so that I might take up the role not of the heroic bug buster and avatar of order and cleanliness, but their unseen client. The owner of the shamefully pestilent dwelling, finally making the call.

And two people answered the call. I directed them to the smell. I opened my dishwasher. They saw everything they needed to see, and left. And two others came soon after, laden with equipment and dressed for business. At last I bore witness to at least one facet of the presence being simulated behind the House Flipper game camera, and I deferentially stayed out of the way as they set to work, pulling my refrigerator away from the wall with a directness I recognized, as if it were a mere 3D asset in a wireframe world. But this game wasn’t my story, so I didn’t directly see what they revealed: only that one of them immediately hunkered down and set to work, using both hands to attack something. Her partner struck up a conversation with me about city politics before I became too curious, nudging my unhelpful attention away from the work area: a touch of benign social engineering for which I can only be grateful.

Things continued in this vein for some time, requiring another followup visit or two, before the roaches were seen to and their hideouts made sufficiently uninviting to discourage any rival clans from moving in afterwards. And I haven’t played House Flipper again since then, either; doing so would still feel a little… redundant.

I’m still intrigued by the potential of experience-focused simulation games. I mentioned American Truck Simulator earlier, in part because a dear friend has encouraged me to try it, putting myself—a Manhattanite who rarely gets behind the wheel anymore—into a voluntary highway hypnosis as a pleasant way to relax. I see the appeal of that too!

But I expect that it will be some time before I replicate my experience with House Flipper, where I play only about five percent of a game, and yet end up feeling that I won it… so transcendently.

This has been Venthuffer. You can learn more about this show, and find links to the things that I mentioned in this episode, at Venthuffer dot com. And you can find me on Steam, as Halstrick.

We got rid of that dishwasher, by the way.

The Steam Deck has a one-button suspension feature that lets you safely set the console down and immediately turn your full attention to something else, at any time, even in the middle of a game. Even though this is one of the best features of the Deck, it’s in tension with another feature, one that can make instant suspension effectively unusable. This episode is about how I had to discover this for myself, and buy my way out of it.

This episode was inspired by a conversation I had with the hosts of The Short Game podcast on an episode about the Steam Deck that they kindly invited me to join.

Things mentioned or alluded to in this episode:

- The Medium is the Massage: An Inventory of Effects by Marshal McLuhan and Quentin Fiore

- Persona 4 Golden

- Caves of Qud

Starting with this episode, I have changed the tagline of the show from “A dream of the Steam Deck” to “A reverie of the Steam Deck”, for various reasons. Thanks to Marc Moskowitz for the winning suggestion.

The cover artwork for this episode uses the image “Clifton suspension bridge at dawn” by sagesolar. It is licensed under CC BY 2.0 .

Full transcript:

They don’t put it on the box, maybe because there’s no way to boast about it with numbers. It has nothing to do with screen size, or processor speed, or frames-per-second. You have to have used the Steam Deck for a while to realize that one of its key features, maybe its most important—one that elevates it above both ordinary gaming PCs and handheld systems of the past—is how quickly you can make any game stop.

This is Venthuffer, a reverie of the Valve Steam Deck, by Halstrick.

Today, my home has two Steam Decks in it, purchased about two years apart from one another. The second one is a newer model, but that’s not why I bought it. I bought it because, so long as only one Steam Deck was in the house, nobody living here could use one of the console’s best features. That’s the ability to instantly and wholly suspend whatever you’re doing with one click of the power button on the top of the console—or, if you’re using a Bluetooth controller, with a short sequence of button presses. So long as the console doesn’t run out of battery power, you can resume play instantly at any time by pressing that button again.

It works like a dream. Or, rather, it’s dreamless, despite being formally called Sleep mode. From the point of view of the game running on the console, play continues uninterrupted on either side of the suspension, heedless of time suddenly skipping ahead in the real world.

But this feature is in conflict with another, one that Steam Deck seems to possess only begrudgingly, because its presence is expected on modern game consoles. The Deck lets you create multiple user profiles on a single device, if you want to, each tied to a different Steam account, and makes it relatively easy to switch between them. However, switching profiles essentially means rebooting the whole device, which wipes away any suspended game.

Now, there’s nothing inherent about the mere presence of a second player profile on the Deck that prevents Sleep mode from working exactly as intended—at least, not until the point when that second player asserts their right to have a turn with the machine. In households like mine, containing two people with boundless love for one another but fiercely independent gamer identities, this introduces friction.

The problem rises not from the mere act of sharing, a central tenet of any long-term partnership which, I dare say, never hurts to practice more. Instead, it creeps in, over iterations. Watching your beloved play the game that brings them joy means that when your turn comes around again, you won’t be able to click the power button and resume your game in the same moment where you left it, as you can when striking out solo with Steam Deck. No, you’ll need to spend whole minutes flipping the system back into your account, watching boot-up animations, selecting your game, wading through all of its own various startup screens, and then finally going through whatever in-game warmup you need to accomplish before you can finally resume play. And the whole time you’re doing it, you know that you’ll just need to do it all over again at the start of your next session. And you’ll come to wish, more and more, that you could just click that wake-from-sleep button instead.

This can fester, friends. This can turn the act of sharing a thing you love with a person you love into something ugly. It can start to feel like you’re being denied a thing you deserve. Imagine sharing your home and your game console with a partner who is just as into the Jungian teen hijinks of Persona 4 Golden as you are into the procedurally generated fungal infections of Caves of Qud, and rather than see this delightful absurdity as something to celebrate and bond further over, it becomes a gateway into quietly seething resentment.

That’s no way to live. And that’s why I bought my partner a new Deck for Christmas.

The quiet perfection of the fast suspend-and-resume feature shows how the Steam Deck is designed not to desire all of your attention, and presses this generosity into all of the games that it runs, regardless of their own design. The Steam Deck wants you to be able to put the game aside immediately and with no hard feelings whenever a loved one in your vicinity needs your attention instead. You click the button and set the device down, knowing you can pick it up again when you’re ready, and with no penalty to pay in lost progress, or time wasted to startup ceremonies. And this knowledge lets you put your game out of mind completely, shifting your attention entirely to the the person or thing that needs it in the moment.

But even if the unjealous Steam Deck doesn’t want all your attention, it wants the attention of nobody except you. Its surface design might say, “Oh, no no, I don’t mind being shared, add all the accounts you want, no problem!” But in its heart, it wants to be a personal device. I refer to its heart almost literally, or maybe I should say its guts. If you drop into Steam Deck’s so-called Desktop mode and dig around its underlying Linux operating system, you’ll find that, no matter how many Steam user profiles you add to your Steam Deck, there remains only one actual user account on the machine. That user has the login name: “deck”, in all lowercase. This is interestingly ambiguous, isn’t it? Does this user represent the Deck’s human operator, or the deck itself?

I find this confusion very suggestive. The design of the Steam Deck intentionally mingles these notions. If I can risk borrowing a page from Marshal Mcluhan here, the Deck wants to be part of your personal identity by becoming a extension of your body, in the same way as the car you’re driving is an extension of your feet, or—more the point—how the smartphone in your pocket is an extension of your central nervous system. This isn’t novel to the Deck, it’s a natural fit for any successful media device.

And I would claim that the Steam Deck’s success at becoming part of your extended body pivots around its ability to suspend play and then resume it again with hardly more mental effort than that which is required to move your fingers. But as a side effect, handing the device off to someone else feels kind of bad. I may not feel the profound unease I do when someone is scrolling through my unlocked phone, holding a big chunk of my own live and squirming sensorium in their hand, and out of my control. But it still doesn’t feel good to loan out hardware that, even in a lesser way, feels like part of me. And lest I be accused of solipsism, I acknowledge that other users of the shared Deck can’t help but feel exactly the same while I’m enjoying it.

It’s kind of a shame that the designers of the Steam Deck feel the need to maintain its traditional-console front by having it masquerade as a multi-user system. The Deck works best when treated as a sort of cybernetic limb that you can flex to express a personal playfulness. By making the act of putting it down so painless, the Steam Deck’s design helps you make room for a richer life, full of things deserving your attention, something that suspension bridges.

This has been Venthuffer. You can learn more about this show, and find links to the things that I mentioned in this episode, at Venthuffer dot com. And you can find me on Steam, as Halstrick.

On Balatro, and my diminishing personal susceptibility to videogame addiction—even when I invite it in.

Things mentioned or alluded to in this episode:

- The Salmon Walk in Ketchikan

- The Sealaska Heritage Institute in Juneau

- “Shipping Out” by David Foster Wallace, better known by its reprinted title of “A Supposedly Fun Thing I’ll Never Do Again”

- Nethack.org

- The first trailer for Balatro

- The Steam store page for Balatro, which includes the second trailer video that I mention

- The mobile-version teaser trailer for Balatro

Full transcript:

What began as an embrace of nihilism in a desperate attempt to feel something while disconnected and adrift ended with a discovery of… nothing in particular. And the subtle difference between those two varieties of absence held a profound relief.

This is Venthuffer, a dream of the Valve Steam Deck, by Halstrick.

I don’t need to dive deep into the reasons I didn’t have a great time during the interminable “sea days” of an Alaskan cruise last summer.

Really, I enjoyed our ports of call very much, from Ketchikan to Juneau, and I can go on at great length about my new appreciation for salmon, both as a meal, and as a symbol for the presence of the divine in nature, especially as represented in the ubiquitous formline artwork of the Pacific Northwest’s indigenous peoples.

The sea days, though, held little to inspire me. While I did pack a book or two, the prospect of being sealed in a bobbing vessel with no internet access and surrounded on all sides by the very same shuffling Trumpian decadence well documented in a famous essay by David Foster Wallace had me all but climbing the walls of my stateroom before dinnertime on day one.

This is when I resolved to do something that, for the past several months, I had forsworn. I pulled our Steam Deck from the luggage, and for the very first time, I fired up my partner’s copy of Balatro, which had launched earlier in the year, and which I had until that moment willed myself to avoid based on the reputation that it had immediately garnered.

Here’s what I thought would happen: Feeling, again, addiction as something almost physical, a fitlhy goblin that I invited to nest in my brain, its fist clutched around the nearest knot of axons. With a sharp yank, it could pull my attention back to the game, again and again, feeding it all the electricity of my faculties in exchange for keeping me numb to everything else, including the passage of time. With land nowhere in sight, it’s what I thought I wanted.

As you might infer, I have a certain history with profound video game addiction. I touched on it, indirectly, in episode five of Venthuffer, the one about Permadeath. I’ve never been one to fall under the sway of games that massage you with the sort of mild, unceasing success offered by Bejeweled and its ilk. Rather, my poison has always come in the form of Roguelikes. And, the Roguelikes know this.

“Thank you for the latest release of gradewrecker. My GPA just went in the corner and shot itself,” says the front page of Nethack, as it has for decades, quoting an early, anonymous addict of the venerable dungeon crawler. So it was for me, especially in my 20s and 30s, losing days or more to the endless chase for make-believe “experience points”, enumerated as an meaningless integer and graduated into arbitrary “levels”, and the narcotic pleasure of working hard for hours at a time for no external reward other than simply watching those numbers just… go up.

Balatro didn’t necessarily launch with the attitude that Nethack has, but very quickly grew into it and then far surpassed it, something you can track through Balatro’s progression of official trailers throughout 2024.

The Balatro launch trailer is a typically peppy introduction to the game and its own spin on deckbuilder mechanics. The trailer I first saw, though, shows how the Balatro team quickly adopted a more focused idea of who the game appealed to, stuffing the video with critical quotes about the game’s addictive qualities, and—most alarming to me—a slow zoom-in on a score-counter as its numbers grew larger and larger and caught on fire, the result of a particularly strong play. That is to say, a shockingly naked appeal to those with a certain susceptibility to seeing a number going up. Months later, the announcement of the game’s mobile version had become an overt, swaggering troll. The video intermixes bewildering flashes of gameplay footage with anxious horror-movie sound effects and shots of players weeping in despair while the publishers cheer in triumph. The teasing grin of the game’s mascot transforms into a dreadful, close-up leer, boasting of the game’s mental domination over its paying audience.

And, as the north Pacific wind whipped over me, lying alone on the promenade deck, clutching my Steam Deck in freezing fingers, I chose to willingly submit to all of it. Anything to keep me alive until we anchored at Victoria, B.C. I launched the game. I played the tutorial. I let myself drift.

It was… fine. I mean, it’s a good game. I admired the design, but to my surprise, it didn’t really speak to me. The most negative thing I felt was mild frustration at losing again and again, without the ever-present tug towards a distant but seemingly attainable victory that I have long expected from roguelikes. And so it just became a merely interesting passtime, and not the sucking void that I was promised by its own marketing materials.

After returning home, my partner taught me some basic Balatro strategies, letting me achieve my first wins. I found myself appreciating and even enjoying the game a bit more. And this feels like where the story should take a dark turn, but, no, not here either. My total playtime with Balatro has yet to surpass 20 hours. I do still pick it up now and again, but just for the sake of variety between other games or activities. The goblin never moved in.

And it’s not just Balatro. I’ve become reacquainted with Caves of Qud since I last spoke about it on Venthuffer, playing in pleasant bursts as time and interest allow, and disinclined to let it hook me again. I’ve also played the first few chapters of the 2024 JRPG epic Metaphor Refantazio, and while I know my younger self would have been completely parasitized by its expertly engineered treadmill of overlapping quests and ever-rising levels, I felt pleasantly full and pushed back from the table somewhere in the high teens. I’m sure I’ll dip in for another visit when I next have an appetite for that particular sauce, though I’ll lack the desire to drown in it.

I have a hypothesis about the relevant changes in me that have allowed me to casually stroll through games that were once bear-traps for my time and attention. In the past, when I knew I was making poor use of my time at a game that I kept picking up anyway, I would sometimes mutter out loud: I can feel myself getting older. This was an inexperienced way of expressing a lament that I’ve since become more familiar and even comfortable with: my time and attention are my most limited and precious resource. The notion of “wasting time” seems like such an anodyne scold when one is young, like “wasting water”. My growing awareness of my attention’s finitude has, I think, weakened the ability for any video game to wholly subsume it for very long.

But there’s something else too, both subtler and, in a way, more real. Video games have always been important to me, a primary route to staying playful. But I’ve come to value them more as experiences than challenges. Today I have as much desire to spend hundreds of hours with any one game as I would with any one book, or film. Certainly some rare examples might deserve that much attention, but generally I prefer to acknowledge, appreciate, and maybe even savor the unique experience that a game has to offers, and then move along. Maybe that happens at a credits-roll, and maybe that happens when the game seems to start repeating itself. I set it down with gratitude, I push back, I move along.

And I let myself take pleasure, even eagerness, in having something to move along to: Maybe another game, or some other media, or maybe a completely different vessel for my attention: spending time with a friend, or taking another swing at learning piano. Or, yes, writing out a podcast script!

Experiences have a lasting physical component, you know. Novelty, and discovery, and learning, all score themselves in the white matter of your brain, making connections that change you in the most literal sense possible. Even if I can’t see a number tallying of how many neural pathways I’ve grown, I increasingly suspect that it’s the only number-going-up in my life that I ultimately care about. I’m not saying that I have the antidote for the stagnation of game addiction. But I have realized that, for me, the way to keep that goblin away from its nest is simply… to crowd it out.

This has been Venthuffer. You can learn more about this show, and find links to the things that I mentioned in this episode, at Venthuffer dot com. And you can find me on Steam, as Halstrick.

Coming in just under the wire of the spring-equinox deadline I set for myself last time, I’m happy to say that Venthuffer season two launches this coming Monday, March 17. Find the first episode that day here on venthuffer.com, or on your favorite podcast app.

I plan to release subsequent episodes with the same regularity as before, but at a slower pace: probably biweekly. The weekly frequency of season one felt appropriate at first, but as the zine found its shape and footing, episodes got longer, and took me longer to make. That’s not changing! So, I’d like to give them a little more breathing room, which I think will make for a better show.

I very much look forward to sharing these stories with you soon.

Hello, dear Venthuffer listener. I am retroactively declaring that the previous six episodes constitute season one of this audio zine. One consequence of launching a weekly publication in October is that no sooner does the show start to get its legs under itself, than the wintertime holiday vortex arrives to sweep those same legs away.

I am very pleased with our initial episodes. Even though I fell short of my entirely arbitrary goal of ten issues, I did meet the six-episode high-water mark set with my previous monologue project. And I find that I have a lot more to say about the Steam Deck and points adjacent. But the work deserves my full attention, and I can’t quite manage that while otherwise gearing up for the year ahead.

So, Venthuffer is going on a short break, to return… sometime in early 2025. Before the equinox in March, let’s say. If you subscribe to Venthuffer in the podcast app of your choice, then you’ll be the first to know when it returns. And you can always keep tabs at venthuffer.com, where, yes, there is a full RSS feed, if that’s how you swing.

Until then, happy holidays, enjoy the Steam sales, and make time to play attentively with the games and the people that you love. And you can find me, on Steam, as Halstrick.

On UFO 50 and ever-flowering cycles of the simplest game designs.

Things mentioned in this episode:

- Spelunky

- UFO 50

- Carl Muckenhoupt’s post

- The Eggplant podcast discusses Magic Garden

- Jim Stormdancer’s critique

- Wikipedia’s article on the Snake game genre

- Snak by Zach Gage and Neven Mrgan

The cover artwork for this episode uses the image “Nokia 3310 mobile phone, 2000” from the Science & Society Picture Library.

Full transcript:

A six-person, eight-year project helmed by Derek Yu after he made bank with Spelunky in the early 2010s, the absurdly audacious work called UFO 50 gives us a pirate ROM cartridge from an alternate universe. It contains fifty wholly original video games for an entirely notional 1980s console, spanning the complete ludography of UFO Soft, a game publisher that never existed.

Carl Muckenhoupt quipped online that: “The basic fantasy behind UFO 50 is having something that’s like your Steam library, but of manageable size.” Much like my own real Steam library, I suspect I’ll never thoroughly explore every corner of UFO 50—and this is hardly a complaint.

Initially released on Steam for Windows, UFO 50 fits perfectly on the Steam Deck, transforming your hand-held device into a Game Boy from another dimension. And one of the many joys I have so far discovered within its collection is a slippery and disguised adaptation of a ubiquitous yet seldom discussed mobile game with a particularly cyclical history.

This is Venthuffer, a dream of the Valve Steam Deck, by Halstrick.

If we wish to play along with the fiction of UFO 50, it’s better to think of it as a visitor from an alternate reality than a forgotten historical artifact.

The developers have adhered to the spirit of the 80s in some ways. The aesthetics are more or less believable. While some of the more modern character designs stretch credulity, all of the games’ visuals comprise relatively simple sprites and color palettes, and the audio is entirely ruled by the square-wave effects that we still associate with the era. At least as significantly, the control scheme is strictly that of a mid-80s console: An eight-way D-pad, two action buttons, and that’s all.

But the authors of UFO 50 gave themselves far fewer restrictions on pinning the games’ design to their putative era. For example, the game called Rock On! Island is unmistakably a 21st century tower defense game, and Party House is a solitaire deckbuilding game, relying on a tabletop mechanic that wouldn’t exist until nearly 2010. They’re both good games, and honestly? Their overt anachronism is part of the fun!

When arranged in their default faux-chronological order, the collections’ first and last games both feel like much more sincere attempts to emulate designs popular in their respective quote-unquote publication years. The very first game, Barbuta, is a mulishly janky pre-Mario Bros. platform game, and Cyber Owls is an entirely believable cash-in on the late-80s craze for ninja-turtles clones. These two bookends give the other 48 games period-appropriate cover—literally!— to get a little historically unbound with their mechanics, which I find delightfully clever.

This sets the table for one of my favorite titles of the collection, even though it’s one of the simplest. Magic Garden is the fifth of the fifty, and has the look of a simple arcade game. You control a little girl who skips around a square playfield, collecting cute, blobby creatures called Oppies and leading them into safe zones, while avoiding obstacles.

But things start to feel a little off pretty quickly, especially if you have any experience playing actual arcade games of the early 80s. It will probably take you mere seconds to discover that you have only one life. You will learn this when the girl careens into a wall, which knocks her down and ends the game instantly. At first, this feels bad! Jim Stormdancer has critiqued this single aspect of Magic Garden as betraying the kayfabe of the entire collection, noting—quite correctly!—that any game of the era would certainly give you three lives, enough to feel like you figured out things at least a little bit before your first game-over.

But it’s also a clue.

Despite my own initial bafflement with Magic Garden, I was interested to see folks in Discord, on Mastodon, and on gaming podcasts really hone in on analyzing this game, even though it’s hardly the deepest design in the collection. However, it is arguably the first of the UFO 50 games that feels good to play, if you’re approaching the collection chronologically, the first one that isn’t intentionally designed to feel juddery and dated. Once you brush aside the single-life quirk the appeal is immediate: Save oppies, stay alive, and get that score as high as you can!

So, I kept Magic Garden on my UFO 50 play rotation. And at some point, I tried it during phone calls with older members of my family, who naturally ask of me a hundred-to-one listen-to-speak ratio. It became immediately clear that this was how the game wanted to be played: in fidgets. Curled on my couch, AirPods in my ears Steam Deck in my hands, I could contentedly hit that start button dozens of times in the span of one thirty-minute call.

And soon I realized: Oh, it’s Snake. The game is just a variant of Snake, straight from my old Nokia’s cracked LCD screen to you. And then everything makes sense. Of course you don’t have lives in Snake! Why would you? Snake is designed to pass just a few moments before your inevitable game-over, and if you want another bite of Snake after that, my all means press the button and carry on. In case there’s any doubt, the true identity of Magic Garden is given away by the on-screen word “Oppies”, which in retrospect is a typographical blur of “Apples”, the things you try to collect in the classic flip-phone game. A sublimely subtle checksum.

With the scales fallen from my eyes I could see that Magic Garden is actually a perfectly clever and quite original twist on its progenitor. You don’t just eat and grow until you die. The length of your snake-which is to say, the little girl plus the train of collected oppies following her—grows and shrinks as you collect and deposit the creatures. Obstacles continuously spawn, but every time you meet a dropoff quota you receive a powerup which gives you a brief window to clean up otherwise deadly enemies.

This means that you’ll occasionally encounter satisfying moments where you clear everything on the screen, and can collect oppies at leisure for a few luxurious seconds before meanies start spawning again. You end up living for these natural pauses, and they always feel great.

You’ll still die because you miss a turn, or something hemmed you in, or you just got unlucky. But again: Snake. There’s no sense of lost progress. The high score table is just there as a pole star to aim at. The game is a meditation, a voluntary focus for your attention on something immediately present, with frequent breaks.

Magic Garden isn’t even the only new and interesting take on Snake released by a well-known indie-game developer in recent years. I could for instance also point you to Snak, spelled S-N-A-K, which Zach Gage and Neven Mrgan published for the Playdate console in 2023. This one brings a very fun rail-grinding mechanic to the classic formula, and demonstrates how a contemporary game creator doesn’t need all the fictive trappings of UFO 50 to say something new about an ancient design.

With Magic Garden, we have a 1970s arcade game, revived for 1990s cell phones, reinterpreted by a 2020s game, pretending to be from the 1980s, and to which I set the full capabilities of a quad-core three gigahertz hand-held computer. I do have to appreciate how this particular snake has been eating its own tail for about as long as I’ve been alive, suggesting that the art form of video games is now just old enough to have its own multigenerational archetypes of design, with its own demonstrations of how some patterns are just… eternal.

This has been Venthuffer. You can learn more about this show, and find links to the things that I mentioned in this episode, at Venthuffer dot com. And you can find me on Steam, as Halstrick.

Appreciating Caves of Qud as a gymnasium for Stoic thinking.

Things mentioned in this episode:

- Caves of Qud

- Jotun, Who Parts Limbs

- Rogue

- NetHack

- Angband

- A snapshot of my Stoic studies as they stood when my character “Kiyuwumar” met their end

- An example of the Mastodon posts I made during that run

Full transcript:

I know that my best run at Caves of Qud, and indeed any traditional roguelike, happened between the first and fifth of March in 2023. I know this because of the dates attached to the Steam achievements I earned during that run, which today read to me as an inventory of keepsakes found on the body of Kiyuwumar, the Star-Eyed Esper, when their body was recovered from the ruins of Bethesda Susa. Among them, the one that breaks my heart is an achievement earned for befriending the science-genius NPC known as Q-Girl. It depicts her in portrait—a sort of anthropomorphic bear with a punk hairstyle and goggles. My character died so suddenly that I know they weren’t found with Q-Girl’s photograph clutched to their breast. But I think it’s not impossible that, in the split-second of awareness that their end had come, her face was the last thing they thought of.

This heartbreak represents my high-water mark in the roguelike dungeon-crawler genre, and it is likely I’ll never surpass it. I couldn’t bear to even try Caves of Qud again for the rest of that year. When I timidly started to play around with the game again ahead of its long-awaited official one-point-oh release, it didn’t dispel the psychic hurt from my previous run, which I realize I now wear on my memory like a scar, no less real nor more ridiculous than the mark by my right thumb from where the family cat scratched me once in the 1990s. This game injured me. And I can’t recommend it highly enough.

This is Venthuffer, a dream of the Valve Steam Deck by Halstrick.

It was the legendary troll named Jotun, Who Parts Limbs, who killed my Caves of Qud character with a single axe-throw, mere moments after I first encountered him, and while I was just beginning to size up the situation. When it happened, I sat in silence for a long moment, my blood turning to ice. With nerveless fingers, I took one last screenshot, and I knew here I beheld the whole of my practical response. There would be no coming back from this error, no confessor I could call who could tell me how to undo my mistake through meditative toil, or through manipulating data files. For me, the game was over.

As designed! Caves of Qud—that’s spelled Q-U-D and it is pronounced like the cow’s chew-toy—is a traditional roguelike, one that hews close to the mechanics of the primordial computer game literally titled Rogue, a single-player, tactical turn-based dungeons-and-dragons simulator. Qud has several play modes, but the one it nudges you to think of as the true way to play—by making it the default choice on its New Game menu—is the so-called “Classic” mode, where character death is immediately permanent. This game isn’t the sort of roguelike that becomes iteratively easier as you replay it, allowing you to retain or upgrade certain aspects of your character between “runs”. Anything that you carry between Caves of Qud runs is encoded entirely in the experiences and memories of you, the player. The level-one scrub that you roll up at the start of your hundredth Qud run is no more intrinsically powerful than the one you meet the very first time you play.

I’ve been a fan of traditional roguelikes for a long time, starting with twentieth-century classics like Nethack and Angband, though I never made particularly deep progress at any. I’ve been aware of Caves of Qud for some years, but I finally got the nerve to try it after I saw that Steam had marked the game as fully compatible with Steam Deck. Which immediately enthralled me, because seeing that little green checkmark seemed a patent absurdity. Every trad-rogue that I’d ever enjoyed required so many keys in order to issue its umpty-hundred possible commands that it even resisted play on a laptop, which lacks the requisite number pad. But the Caves of Qud developers, beginning their work on the near side of the millenial divide, managed to actually make a dungeon crawler of the ancient mode completely playable with only a game controller. They created a clever scheme which arranges all the commands you need into chords involving the trigger and shoulder buttons. So, to move around, you tilt the left stick in one of eight directions, then squeeze the right trigger. This frees up the right stick for highlighting and learning more about other objects in the world, and the D-pad-plus-trigger for paging through the visual quick-access bar of unusual commands specific to your character’s skills, something informed by MMOs and other, much newer role-playing games.

In addition, Qud mixes in a lot more automation than the ancient games had. For example, the left shoulder button will automatically have your character try to move towards and attack the nearest enemy, regardless of direction, and pressing the Y button while holding the left trigger puts your character into an auto-explore mode that stops as soon as they see a threat.

This sounds like a lot. It is a lot! And yet, if you’re willing to give it enough attention to learn the ropes, it clicks. It’s a good game, developed with care and attention to player feedback over the course of many years. After a couple of sessions, it even starts to get comfortable, and you may begin to feel confident with it! You’ll probably start keying in commands rapidly, learning to read the screen, a sense of mastery starting to creep in.

And that, of course, is how you lose.

Well, I knew the risks, which is to say, no matter how high I flew, I knew the only way that this could possibly end.

When I had that amazing Qud run which ended so abruptly, I had been studying Stoicism for about one year. The philosophy was brought to my attention from a colleague at the very large technology company I worked for at the time. A chief hangup of the ancient Stoics was death, and specifically the purpose of living when death, the erasure of everything, was inevitable. And one way to square that terrible circle is this: Your life is a gift, and it is your duty to respect that gift by making of yourself the best you that you can, given the time and resources available. And because of these studies, I could not help but see that a traditional roguelike as a simulation of this, precisely.

Stoicism counsels its students to locate their own path to developing personal virtue, and to walk that path as far as they can. In a roguelike, the nearest you have to virtue is experience level, and hit points, and ability scores. So be it: it’s an abstraction, but an effective one. Just as in reality, you have essentially no control over the game-world external to your character, but you can do your best to extract experience points from it, and then you do have full control over spending those points to improve your character in some way. Also, you have from the outset an ideal that you can strive for—winning the game. But whether you get there or not—and very probably not—the game will end. It will probably end suddenly, and much sooner than you’d like it to.

So I wore this attitude as best I could, for that one week when I found myself possessing a Qud character that had somehow survived for more than ten hours of play and was well into the midgame, against all odds, gathering up power and potential. I began every session reminding myself that I was ready to die. I would post summaries of my achievements each day to Mastodon, and always conclude with a reiteration of how I already felt peace with the increasingly precious character’s inevitable loss.

So when it happened, I wasn’t sad, or mad. I was devastated, I felt real shock.